As creators of English Language Teaching (ELT) materials, we know that one of the biggest challenges in language learning is remembering new vocabulary and phrases. This is better known as retention.

The secret to retention is repetition. But how can we do it in an interesting way without boring our learners? The answer lies in strategic repetition, embedding the target structures into a range of different contexts. Repetition plays a crucial role in language learning; however, not all forms of repetition are equally effective. We all hate robotic drilling! Repetition ≠ drilling. To make repetition work, the approach must be varied, contextually relevant, and oriented toward real-life tasks.

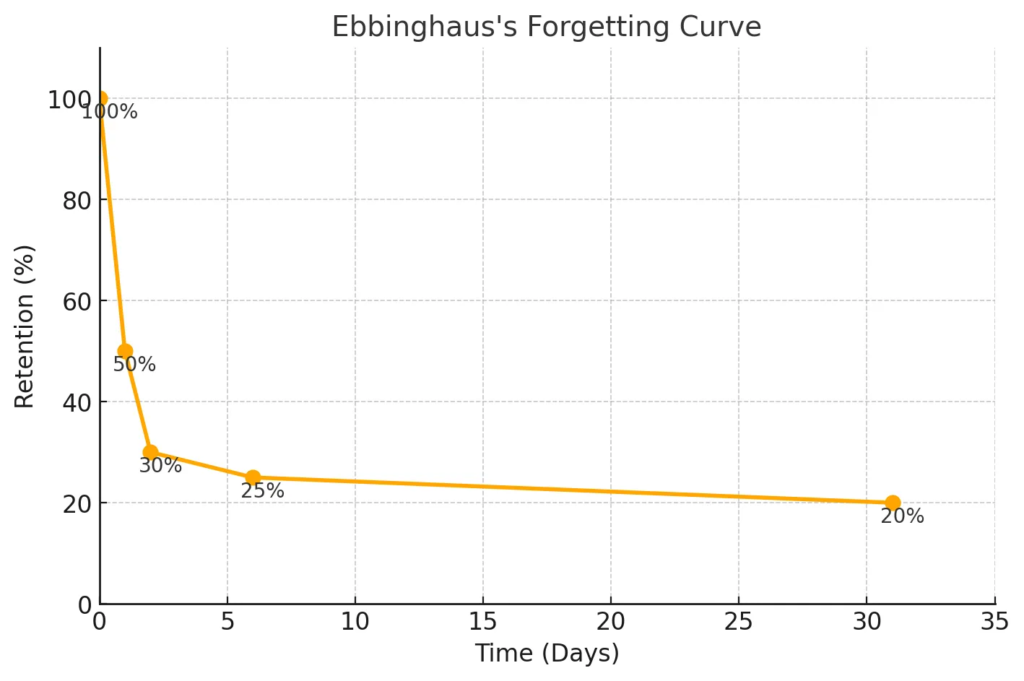

Research in linguistics and cognitive science gives us valuable insights into how repetition supports retention and fluency. Studies show that learners need multiple encounters with a word or structure before they can use it actively. Paul Nation suggests that learners require 6-12 meaningful interactions with a word before it becomes part of their active vocabulary. This is reinforced by concepts such as Hermann Ebbinghaus’s Forgetting Curve, which shows that without repetition, people forget nearly 50% of new information within an hour and up to 80% within days. In other words, this implies that after a month, we only remember 20% of what we learned before. 😢

The key to success is spaced repetition, which involves revisiting the target language at ever-increasing intervals. This helps learners to retain knowledge for a longer time. After each repetition, the forgetting curve levels out, and eventually, learners will retain the item in the long term.

However, simple exposure isn’t enough! To reinforce learning, these encounters must occur in different contexts. So how can we, as ELT writers embed spaced repetition into our materials? One way is to recycle vocabulary across multiple activities. Instead of presenting unfamiliar words in isolation, in a single reading or listening task, we should also put them in follow-up activities. These might include production tasks such as writing, role-plays, or discussions. A word might first appear in a listening dialogue, then be reinforced in a controlled practice task like a gap-fill exercise, and then later reappear in a free production activity like a role play.

Research suggests that retrieval exercises within the first 24 hours of forgetting significantly improve retention. This implies that a good “consolidation strategy” should also be spread over subsequent lessons. In fact, if a student is to repeat after 24 hours, homework tasks and self-paced digital learning exercises come into play. It is necessary to reinforce what has just been learned in class rather than waiting a whole week for the next lesson.

Repetition also plays a key role in grammar acquisition, particularly when combined with comprehensible input. Stephen Krashen’s i+1 theory highlights that language learning is most effective when learners encounter slightly more advanced structures couched in language they know. By exploiting gradual exposure across a sequence of tasks, we help students internalize structures naturally. For example, rather than isolating a new tense in a single activity, we can introduce it through a controlled text, reinforce it in a follow-up dialogue, and then allow for freer practice in speaking and writing.

Another reason repetition matters is that it reduces cognitive load. John Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory explains that when learners are bombarded with too much new information at once, their ability to process and retain it diminishes. Repetition helps lighten this burden by reinforcing previously introduced language, allowing learners to focus on fluency rather than decoding individual words. Scaffolding works wonders in this situation! It can help learners gradually build their confidence and feel great about their progress as they move from easy to more difficult tasks.

Finally, repetition supports independent learning. Lev Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development suggests that learning is most effective when it occurs just beyond a learner’s comfort zone. Like Krashen, the theory implies that learning is best supported by scaffolding. Well-structured repetition helps learners move toward independence by gradually reducing the level of support needed. For example, an email-writing activity that builds on vocabulary from a previous listening task provides a bridge to independent use of language. Similarly, a task-based sequence, where learners discuss a topic and then write about it, allows them to revisit key structures in different ways. This reinforces learning through varied repetition.

Ultimately, as ELT writers, our goal is to balance exposure with task-based engagement. Effective repetition is not drilling, which a lot of people associate it with. It is about giving learners multiple, meaningful opportunities to process, recall, and use language. Make language stick by recycling the target structures across activities and lessons. Language learning does not have to be robotic. The key to ensuring that repetition is purposeful and natural is by placing language in real-world contexts, such as emails, meetings, and conversations. This helps learners see its relevance. Variation is very important! Repetition works best when we mix things up a bit.

Image by Manfred Richter from Pixabay

No responses yet