Discover how communicative grammar teaching transforms adult language learning.

Most adults have bad memories of learning grammar. We were all subjected to heavy, rule-based explanations and grammar drilling at one time or another. The good news is that teaching grammar can be much less boring if we rethink how we do it. So, how does that work in practice? It requires shifting from lecturing students on rules to creating tasks that promote discovery and noticing of grammar patterns.

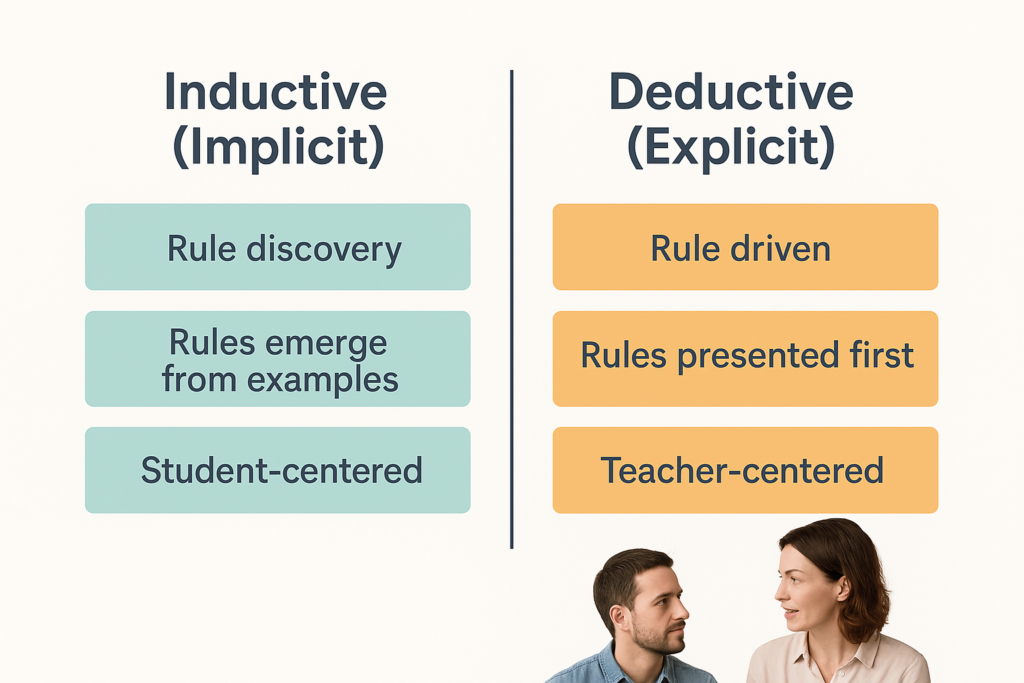

One of the most valuable approaches is inductive grammar teaching. The method proposes that instead of laying out rules explicitly, you let learners discover them for themselves (implicitly). This approach is rooted in Schmidt’s influential Noticing Hypothesis, which states that learners must consciously notice linguistic features in input for learning to occur. Teachers should provide rich examples of a target structure and prompt students to observe patterns and infer rules (Schmidt, 1990).

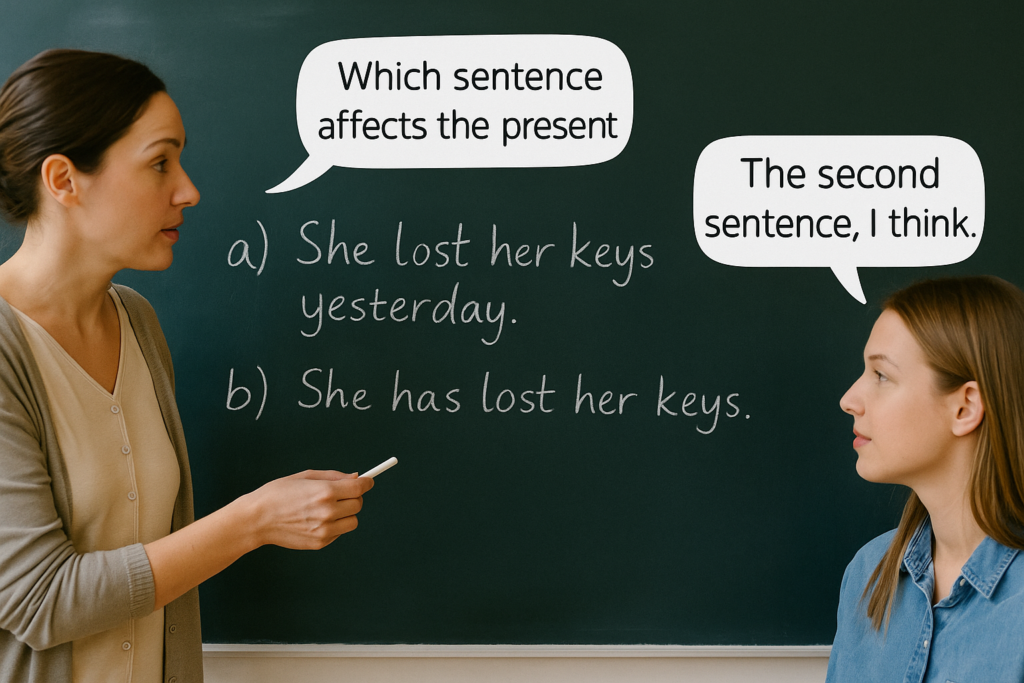

For example, let’s say you’re teaching the difference between past simple and present perfect. Instead of starting with a rule or a chart, write a few sentences on the board: “I lost my keys yesterday,” and “I have lost my keys.” You ask your students to look closely at two sentences and answer simple questions: Which sentence talks about a specific time in the past? Which doesn’t? Which completed action affects the present?

This approach is also known as rule-discovery learning and is aided by consciousness-raising tasks. The inductive teaching concept is that grammar is learned best in meaningful contexts rather than through isolated drills. Trainers use communicative approaches that treat language as a tool for communication rather than an object of study. This is described as a “focus on form” approach: drawing learners’ attention to grammar within communicative activities. Meta language is avoided, including the word “grammar,” which is more loosely described as “language structures.”

This contrasts sharply with deductive grammar teaching, which is all about a rule-first, teacher-led process. Here, grammar is presented as a set of rules, usually explained in detail by the teacher in a frontal lesson. In this behaviorist approach, lessons are strictly sequenced: first, the rule is taught, then drilled, and finally tested. The teacher-centered classroom follows a predetermined curriculum where language is dissected into discrete pieces. It relies on the idea that if students practice a rule enough in isolation, they’ll eventually apply it correctly in real communication. However, research and real-world experience often show this “skills in isolation” method falls flat when learners try to use language naturally.

The communicative approach, by contrast, centers on understanding and expressing meaning. Here, grammar is not the main event but a supporting act. The teacher jumps in spontaneously to highlight a mistake or elicit the correct form. This is called emergent language training: instead of forcing grammar to fit a syllabus, teachers respond to what students are trying to say in the moment. Grammar instruction becomes more incidental than planned, filling immediate needs as they come up in real communication. This engages adults more in an active learning process, which reflects how language is acquired outside the classroom, through noticing patterns, adjusting, and using language to accomplish tasks.

An alternative approach involves teaching grammar through student writing. For instance, tackling grammar issues in real-time within emails and essays often proves more effective than a traditional grammar course. Research has gone a long way to confirm the validity of this assertion. In a 1980 paper, Finlay McQuade argued that conventional grammar instruction has limited value. After conducting pre-course and post-course tests, he concluded that formal, discrete grammar instruction is ineffective. Constance Weaver (1996) advocated teaching only grammar that is immediately relevant to students’ communication. Weaver advocates for a learning model where students actively pursue learning and construct knowledge, rather than passively receiving information. This contrasts with the behaviorist, transmission theory often underlying traditional grammar instruction, which assumes skills practiced in isolation will transfer to writing.

Both authors referred to research that suggests that teaching grammar in isolation has minimal to no practical benefit for most students. Weaver states that “decades of grammar studies tell us that in general, the teaching of grammar does not serve any practical purpose for most students.” She adds that it “does not improve reading, speaking, writing, or even editing, for the majority of students.” The overarching principle of both educators is that grammar should be taught as a function of communication, rather than as a separate, isolated subject.

Successful techniques include “notice and name,” which invites learners to notice a grammatical construction in an authentic text and discuss its form and function. Likewise, role-play and real-life scenarios can create a need for specific grammar (for example, students performing a role-play must use the past tense to narrate a story). By debriefing after the activity, getting the learners to reflect on or correct the grammar used, teachers reinforce the rules in context.

In short, communicative grammar teaching ensures that grammar instruction is meaningful, contextualized, and tied to communication.

Sources:

Schmidt, R. (1990). Noticing Hypothesis.

Weaver, Constance. (1996) Teaching Grammar in the Context of Writing

McQuade, Finlay. (1980) Examining a Grammar Course: The Rationale and the Result

Hammond, Kelsey Teaching Grammar in the 21st Century Classroom

Image: Chat GPT

Comments are closed